9 Weird Things on Your Body You Can Thank Evolution For

Updated Jan. 16 2019, 12:30 p.m. ET

There's a chance you, like me, haven't given much thought to your body or its intricate functions since high school bio class. But yesterday, an evolutionary anthropologist by the name of Dorsa Amir took to Twitter to explain all the ways our bodies are living, breathing natural history museums.

"Did you know the human body is full of evolutionary leftovers that no longer serve a purpose?" she wrote before launching into a fascinating explanation of "vestigial structure" we all carry around since our caveman days. From the bumps on our ears to the reason we get goosebumps, read on for 9 ways our bodies (don't @ me) prove evolution is undeniably real.

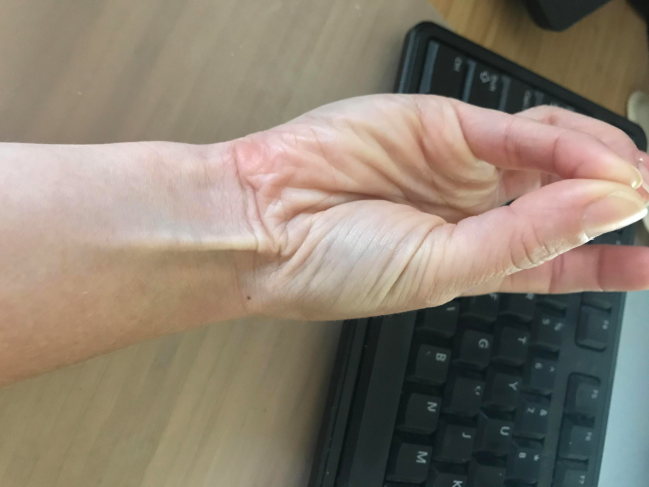

1. The Palmaris Longus

If you put your hand on a flat surface, touch your pinky to your thumb and flex, you might see a "raised band in your wrist." This is called the palmaris longus. Although 86 percent of us still have this muscle, evolution has done away with it in the rest of the human population.

This slender, elongated muscle (it looks like a vein, I know) used to "help you move around the trees, which most of us don't do anymore after childhood. Today, the tendon is often repurposed in other surgeries like Tommy John procedures. Do you still have your palmaris longus? Mine is visible, but very small.

2. Darwin's Tubercle

Darwin's tubercle, also called the auricular tubercle, is a small bump on the inside of your upper ear. Not everyone has these, but they're something like the pointy ear tips found in monkeys, and many evolutionists take this as proof of our shared ancestry with lower primates.

Back in the day, this little bump on our ears helped us move them around. Now that we have "super-flexible" necks, though, we don't need them anymore. Evolution has done away with them in many people, myself included.

3. The Tailbone

According to Dorsa, the tailbone is one of the "more obvious" human vestiges. It's the only thing that remains of our "lost tails," which were useful (think of monkeys) for "balance and movement in trees." When humans learned to walk, our tails became useless and evolution converted our tailbones to a fused vertebra we now call the coccyx.

Fun fact: We still grow tails as embryos, but "attack and destroy them" in the following weeks. As Dorsa explains, "humans develop a small tail" during weeks 4-6 of embryonic development. "During weeks 6-8, the embryo sends white blood cells to dissolve that tail," and the process is called phagocytosis.

4. The Plica Semilunaris

The small pink tissue on the inside of your eye is an evolutionary leftover that used to function as a third eyelid, which used to blink horizontally. These third eyelids are still present in animals like birds, fish, marsupials, and cats.

Today, this vestigial plica semilunaris gives us greater rotation of our eyeballs and helps maintain tear drainage out of our line of sight. Just think: back in the day, our eyes used to blink both ways! People on Twitter are saying they've seen their cats do this, so be extra attentive to yours, if the plica piques your curiosity.

5. Goosebumps

You know how you get goosebumps when you're cold and the hair on your skin stands on its end when you're really scared? This used to be super useful, back in the day. Goosebumps are actually a vestigial reflex that used to trap an extra layer of heat for warmth.

And the raised body hair is another reflex activated in situations of fear and confrontation that allowed us to appear larger and more threatening to predators. Dorsa notes this function "may still work to a small degree, as some vestigial structures still serve a reduced role."

6. The Palmar Grasp Reflex

The palmar grasp is another cool reflex that we've inherited from our primate ancestors. "If you place your finger on an infant's palm (or feet!), they will try to grasp it," Dorsa explains. Primates "would have used this to grasp on to their parents for transport."

This reflex, which has a lot of value during mother-child bonding, disappears at around six months, and is thought to be a useful tactile and visual cue which "communicates the baby's expectation to the caregiver who then reciprocates the grip," another doctor added on the thread.

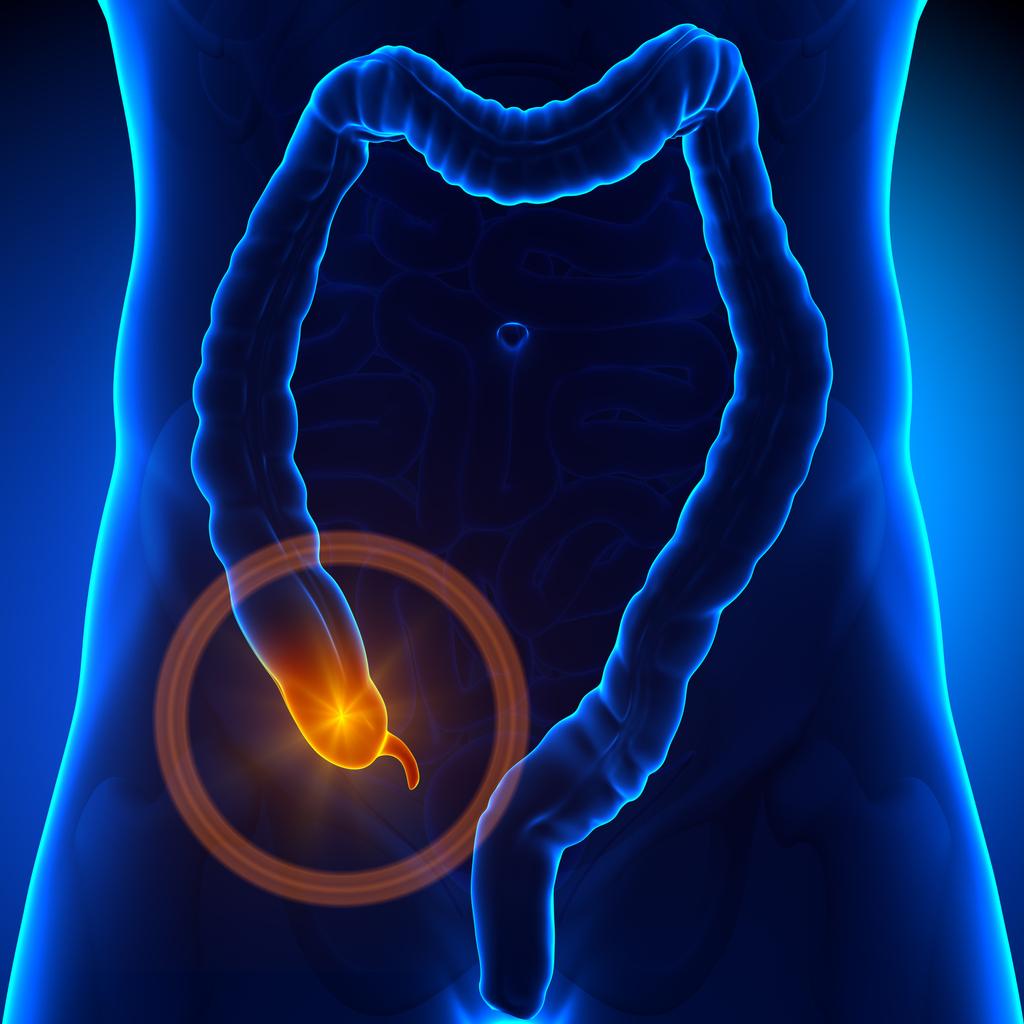

Dorsa concludes her informative thread by adding other examples of evolutionary baggage we carry around. Appendices, for example, seem to have been repurposed to store our beneficial bacteria, but they used to aid in digestion. In fact, plant-eating vertebrates use it as an integral part of their digestive system.

Wisdom teeth, additionally, might serve whatever purpose they used to (adults would have lost many of their teeth before the days of tooth brushing, and wisdom teeth would have kicked in to help), but these days, they've become more of an obsolete pain than anything else. And finally, Dorsa addressed male nipples, which are not quite vestigial but are technically non-functional.

It may come as a surprise to you that men have nipples because of embryonic development. In other words, the gender of a fetus could go either way in its early days in the womb and fetuses essentially start out as female. Eventually, testosterone kicks in and causes a fetus to become either male or female. This is why some men have been known to lactate, and why breast cancer is a possibility among males.