The People Who Lived to Talk About Jonestown Were Forever Changed by What They Saw

One of the Jonestown survivors said thinking about the dead children made her want to "scream her lungs out."

Published June 17 2024, 4:57 p.m. ET

Content warning: This article discusses tragic child death.

On Nov. 18, 1978 in a village in Guyana, South America, more than 900 bodies were found. They varied in age and background, and at first glance, it appeared as if most of them died by their own hands. It would later be revealed that regardless of how some of the individuals passed away, this was the scene of hundreds of murders. Later it would be called the Jonestown Massacre after the man who lured all of these souls down to their deaths.

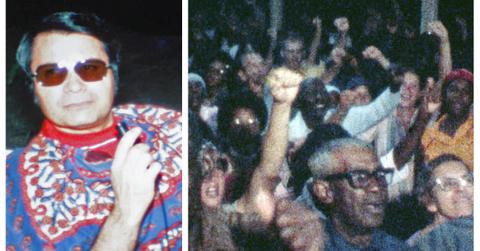

Jim Jones was a power-obsessed drug addict with a God complex, but to many he was a guru and a savior. Unfortunately his actions weren't altruistic in nature, especially on the day he forced his followers to meet the maker of their choosing. And while the scene itself was deeply traumatizing for the first responders, it was even more harrowing for those who made it out alive. Did anyone actually survive Jonestown? It depends on what you mean by survive.

Did anyone survive Jonestown?

Of the 918 people who died both in Guyana and out, as not every member was living in South America, TIME Magazine reported that over 80 survived. In an effort to give a voice to those who didn't have one, author and playwright Leigh Fondakowski (The Laramie Project) spent five years interviewing the people who survived Jonestown. She put their experiences into a book titled Stories from Jonestown which sought to help others understand how they came to believe in what Jones was peddling.

What Fondakowski discovered is that a disproportionate amount of those who died were Black. They were trying to build better lives for themselves and for their children by escaping from a country that did its best to drag them down. Jones preached a faith that was inclusive and non-judgmental, and in doing that, attracted the oppressed and disenfranchised.

According to the IndyStar, only one person ultimately survived the actual murders in Guyana and it was a 73 year-old woman named Hyacinth Thrash. She met Jones in 1957 through her sister Zip who did not survive the massacre. Born in 1905, Thrash lived in Alabama during Jim Crow where 71 lynchings were carried out during the 13 years she resided there. By the time she met Jones, Thrash was in a place in her life where kindness was currency, and Jones was very kind.

In 1988 Thrash spoke with a reporter from the Anderson Herald-Bulletin and told them that Jones "put coal in Black folks’ bins and give them ’em shoes and things. Always willing to help somebody." Because she too was interested in helping people, Thrash sold her house and gave the money to Jones. She and Zip followed him to California and then onto Guyana, where Thrash left without her sister. She was one of two people who walked out that day. The other survivor died a year later.

What happened at Jonestown stayed with the first responders.

A lot of reflection came with the arrival of the fortieth anniversary of the Jonestown Massacre. A few of the first responders who spent months cleaning up the site spoke with TIME in November 2018. They were mostly members of the U.S. Military who might have been used to such a grisly scene, but it was somehow far worse than what they had previously encountered.

What separated Jonestown from something they might encounter on the battlefield was the fact that they were all civilians, and as such, required people from various departments to sort things out. Many were struck by the hundreds of children's bodies they had to contend with. "Can't sleep," wrote one person in a report. "Cannot get the small children out of my mind."

When the Air Force studied the impact the cleanup had on members of the military and civilians, many people spoke about the smell. By April 1979, there were still hundreds of unknown bodies, some of which were too decomposed to identify. In 1995, Thrasher told the IndyStar that she could still "remember those babies marching past our place with little paper hats on, wearing sandals, sun suits and matching shorts and tops." She said thinking of them as dead was "enough to make you scream your lungs out."