At the Behest of Cult Leader Jim Jones, Over 900 People Died at Jonestown — Is It Still There?

Decades after the Jonestown Massacre, a Guyana company was offering tours to the once massive compound.

Published June 13 2024, 5:16 p.m. ET

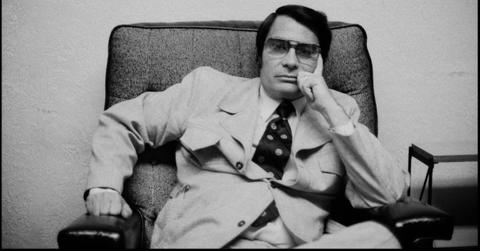

Jim Jones

Specific locations can hold a lot of spiritual weight, depending on what happened there. For example, more than 3 million people visit the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Lourdes in southern France each year looking for a miracle, per CBS News. Many throughout history have reported healings taking place there. On the other side of that exists the power a tragedy can hold over a community. John Wayne Gacy was arrested in December 1978, and by April 1978, his home where 26 bodies were buried was razed.

It's easy to see why a site filled with so much horrific violence would be unwelcome. One of the most infamous examples of a soul-crushing disaster is what happened at Jonestown. Over 900 people died when cult leader Jim Jones ordered them to end their lives, though some rebelled and were quickly murdered. Does Jonestown, and the religion they followed, still exist?

Aerial photograph of the site of what would later be known as the Jonestown Massacre

Does Jonestown still exist? Yes and no.

In September 2018, nearly 40 years after the murder-suicide of 918 individuals, many of whom were children, Vice spoke with two people who had separately visited the place where it happened. Journalist and author Julia Scheeres visited in 2008, while University of Baltimore associate professor Aaron Oldenburg traveled there two years later. They provided valuable insight on what was happening in Jonestown decades after it became a graveyard.

Both Scheeres and Oldenburg had to make the trip down to Guyana, South America, where Jones had relocated his cult from Indiana in the 1970s. They were called the Peoples Temple, and at the time, they described themselves as a congregation. Construction started in the early part of that decade though everyone wasn't fully relocated until 1977. The impetus behind this move was Jones's desire to escape the mounting accusations of fraud and sexual abuse lodged against him by the press.

After Jonestown was cleared out, Oldenburg learned that the locals moved back into that area. They attempted to clear out the site but had to leave certain things like arrows as they had been dipped in cyanide. In the early 1980s Jonestown was converted into a "refugee camp by Hmong minorities fleeing Lao, as appointed by the Guyanese government" (per Vice), but it burned down a few years later. That's when the jungle reclaimed it.

The entrance to the Jonestown compound in Guyana, South America

Oldenburg claimed the locals have mostly positive things to say about the Jonestown residents but Scheeres disagreed. She heard several folks whisper the words "devil incarnate" when speaking about Jonestown. Many were frightened by what went on there and, in particular, how the children were treated.

We spoke with someone from Rorairma Airways which at one point offered tours to Jonestown, per the Guyana Chronicle. The woman we chatted with said they no longer do that and if someone wants to go, they have to charter an aircraft to do it. She also confirmed that it is indeed still very overgrown and has remained untouched since the early 1980s. "There is nothing there," she said ominously.

Does the Peoples Temple still exist?

According to The Guardian, the Peoples Temple was a mixture of Christianity, communism, and social justice issues that Jones created because he was born with an attraction to "religion, especially charismatic Christian traditions like Pentecostalism." It was unlike most religions of its time due its radical acceptance of anyone who wanted to join. Most of the members were primarily interested in helping their fellow man.

Jim Jones sits next to his wife Marceline (L) along with their adopted children and his sister-in-law (R)

Following the Jonestown Massacre, some people stayed in Guyana for six months in order to help clean and organize the site, per the Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple project. The survivors who returned to the United States were often harassed, bullied, or ostracized. Many found it difficult to build some semblance of a normal life.

Charles Garry, an attorney for the Peoples Temple, filed a petition with the San Francisco Superior Court to dissolve the corporation, which was also facing several lawsuits. That was delayed so that the lawsuits could be handled. A court-appointed attorney broke the organizations assets up and distributed them among the plaintiffs at which point the Peoples Temple was no more.