Dystopia Is Always Just Around the Bend in 'The Twilight Zone,' 'Black Mirror,' and 'American Horror Stories'

Published Aug. 24 2021, 10:37 a.m. ET

In every era, there are new representations of dystopia that reflect their time. In the 1960s and '80s, we had The Twilight Zone. Today, we have American Horror Stories. And in between, Black Mirror took over the dystopian stage.

While The Twilight Zone and Black Mirror lean more towards science fiction, American Horror Stories is definitely more of a fright-fest. Yet, all three render twisted interpretations of the cultural atmospheres that define the times — and create dystopias that shake us.

Dystopia has maintained an unwavering presence in popular media since 1800s literature. Earlier works such as E.M. Forster’s The Machine Stops and H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine created dystopias through “engagement with real-world social and political issues and… critique of the societies on which they focus,'' according to author Keith Booker.

Now, television shows are creating their own versions of dystopias that engage with and critique the world around us.

1959 – 1964: ‘The Twilight Zone’

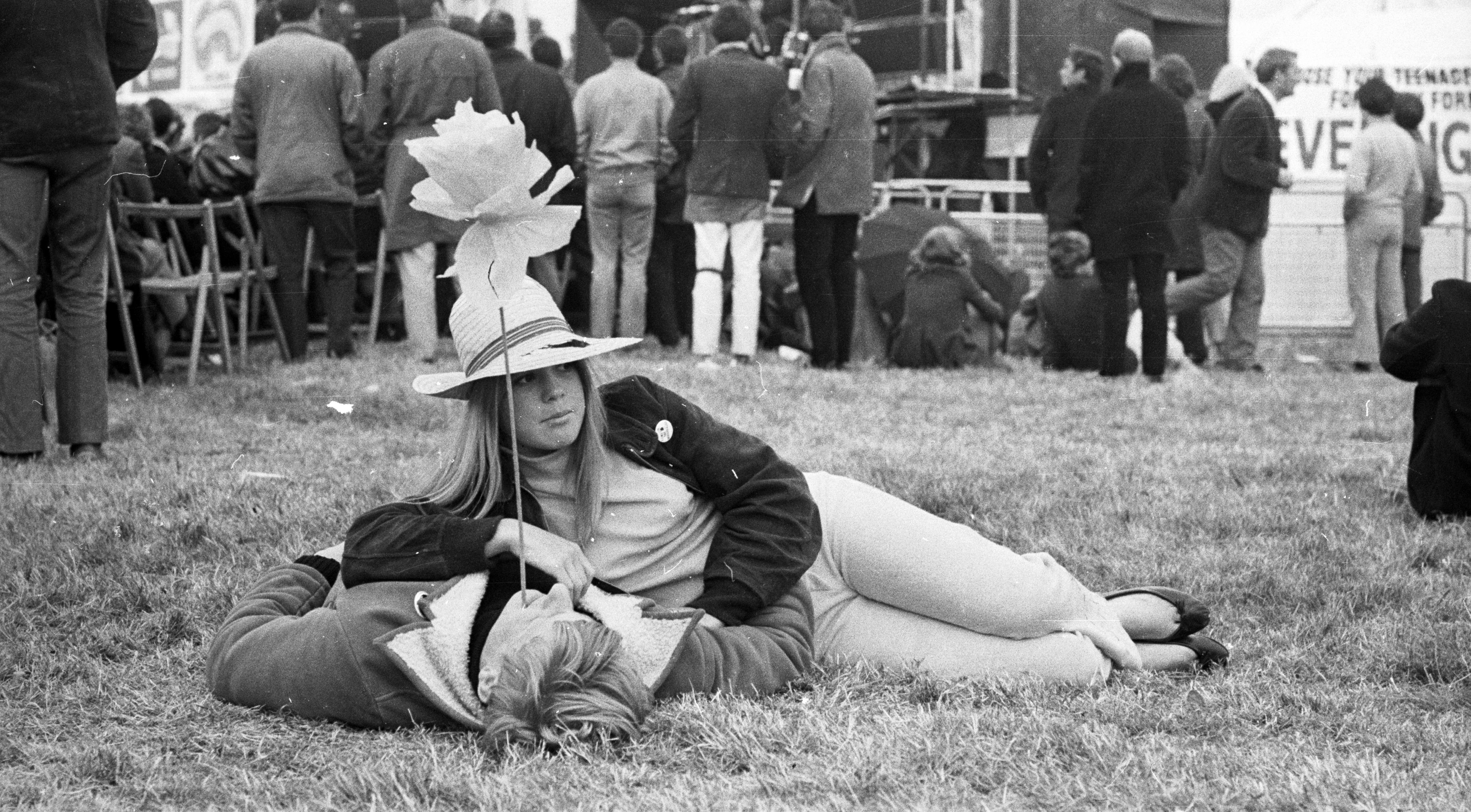

When we think back to the 60s, we think about free love and hippies, Beatlemania, and Barbie dolls and pin-up models promoting unrealistic standards of beauty. But, the '60s also housed the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, and the assassination of JFK, so it wasn’t all love beads and lava lamps.

At the beginning of every Twilight Zone episode, Rod Serling warns, “You're traveling through another dimension… A journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination…”

But imagination took the writers of The Twilight Zone into some very spooky places — places that shined a light on the status quo. Each imaginative journey conveyed a 1960s fascination — whether it be Barbie Dolls or Free Love — gone too far.

The Twilight Zone, like its literary predecessors, critiques society’s obsession with beauty in its very famous episode, “Eye of the Beholder,” in which a conventionally beautiful woman lives in a world where people look like pig-monsters, yet she yearns to look like them to appear “normal.”

She’s sent away to live with people of her “own kind.” This is a clear dystopian consequence of the outer-beauty-obsessed society that defined the 1960s along with the racial segregation that was at the forefront of the civil rights movement.

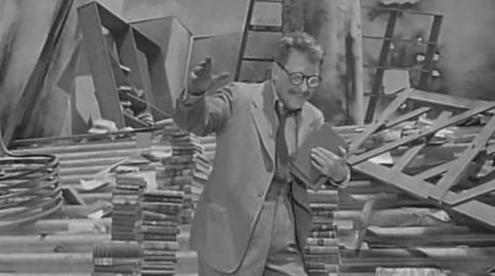

Another famous episode, “Time Enough at Last” chronicles Henry Bemis, who just wants to read books without interruption. When a nuclear bomb destroys the earth, he finally has the time to read unencumbered… until his glasses break. In the midst of war, nuclear weapons were a real threat.

Capitalism and war drive Henry's world to destruction, but the true horror of the episode is the irony behind his glasses breaking. We rely on technology (like glasses) to persist, so even when we want to appreciate the world on our own, this Twilight Zone episode shows that that’s not really possible. We are forced to rely on a world that we might reject and that is the truest form of dystopia.

1985 – 1989: The Second ‘The Twilight Zone’ Series

While the second The Twilight Zone series wasn’t nearly as popular as its predecessor, it continued the trend of showcasing modern-day dystopias. When we think of the '80s, we think of classic coming-of-age stories. Stand By Me. The Breakfast Club. Dead Poets Society. Fast Times at Ridgemont High. Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Diner. E.T. The list goes on.

“What Are Friends For?” stars Fred Savage in a twist on the coming-of-age allegory. Fred’s character befriends an imaginary friend who plays however he wants to, but almost ends up killing him. And when it comes time for him to make real friends, he's unable to.

If we hold all friendships up to the standard of these ‘80s films — in which brotherhood and undying male loyalty reigned supreme — we might never experience sincere friendships. The ideal can never be utopia because ideals and reality exist in juxtaposition.

Building on its predecessor, the episode, “A Little Peace and Quiet,” is definitely a call-back to “Time Enough at Last.” In this episode, a harried housewife finds a gold pendant that she uses to freeze time until a Soviet nuclear missile comes crashing down. While the ‘60s were reflective of the Vietnam War, the ‘80s were prime-Cold War time.

Throughout the episode, the housewife freezes time so she doesn’t have to deal with her “hapless” husband or “rambunctious” kids, but she also skips over the news of impending nuclear doom.

She ignores the world around her to escape her bubbling anxiety, but ends up alone on the verge of an apocalypse. The dystopia exists in the widely held belief that ignorance is bliss — it asserts that negligence and escapism at their utmost supreme are never the answer.

2011 – 2019: ‘Black Mirror’

Black Mirror has been compared to The Twilight Zone before — they’re both science fiction anthology series rooted in dystopian representations of society. A series of the 2010s, Black Mirror feels much closer to home, and is an obvious portrait of dystopia at the hands of technology.

In “Nosedive,” we see what happens when we rely too much on how others perceive us — people are rated by everyone they interact with, and those with higher ratings are given more privileges. This is a clear reference to social media, in which we objectify ourselves to appear likeable, which harkens back to The Twilight Zone’s “Eye of the Beholder.”

Society’s fascination with beauty alone is dystopian in The Twilight Zone, as the episode contemplates the inherent subjectivity of beauty; the Black Mirror episode showcases how technology has transformed such individual subjectivity into quantifiable generalization. Now, social media makes our likability factor objective — we can measure our humanity in likes.

In addition, both “Nosedive” and “Eye of the Beholder” make a statement about privilege and separating people based on how high they rank in society’s ever-changing perceptions of beauty and status.

While the civil rights movement was at the forefront of the 1960s, we are still fighting for justice for those who have been cast down for generations. “Nosedive” examines how hard it is to break the class barrier and creates a dystopia out of a social media-inspired hierarchy.

2021: ‘American Horror Stories’

American Horror Stories, although more horror than science fiction, builds on its predecessors to turn our modern-day world into a gruesome nightmare. Today, many of us love getting lost in true crime podcasts and murderous docuseries. Add society’s obsession with social media and American Horror Stories turns our love of horror into a very meta dystopia.

In “The Naughty List,” a group of vlogging pranksters take their jokes a little too far and end up dead thanks to a murderous Santa. The truly terrifying part of this is that people are watching these boys die and think it’s all a prank. They finally get all the likes and subscribers that they wanted, but they’re not alive to enjoy it.

Like “Nosedive” and even “Eye of the Beholder,” this episode shows what happens when we are forced to cross the line to fit into a world that values status over everything else.

In “Drive-In,” some teens decide to go see the scariest movie of all time, Rabbit, Rabbit. However, as they watch the movie, their brain chemistry is altered, and the audience becomes a mass of flesh-eating zombies, which both parodies and reveres ‘80s slasher films.

Clearly a statement on how our true crime and horror obsessions could turn us voyeurs into the very beings we fear, this episode also ties back to the original The Twilight Zone. A common theme in The Twilight Zone was that dystopia results when the things we desire or fear the most come to life.

In all four series, the characters' wishes, often based on societal whims, come back to bite them. From The Twilight Zone to Black Mirror and American Horror Stories, creators have revealed how society is always laying the groundwork for dystopian futures. And, unfortunately, the common thread is often wish fulfillment: if and when we receive our deepest wishes in their truest form, they're never what we expect them to be.