Nathaniel Woods Shouldn't Have Been Executed — This Documentary Explains Why

Published Dec. 3 2021, 11:16 p.m. ET

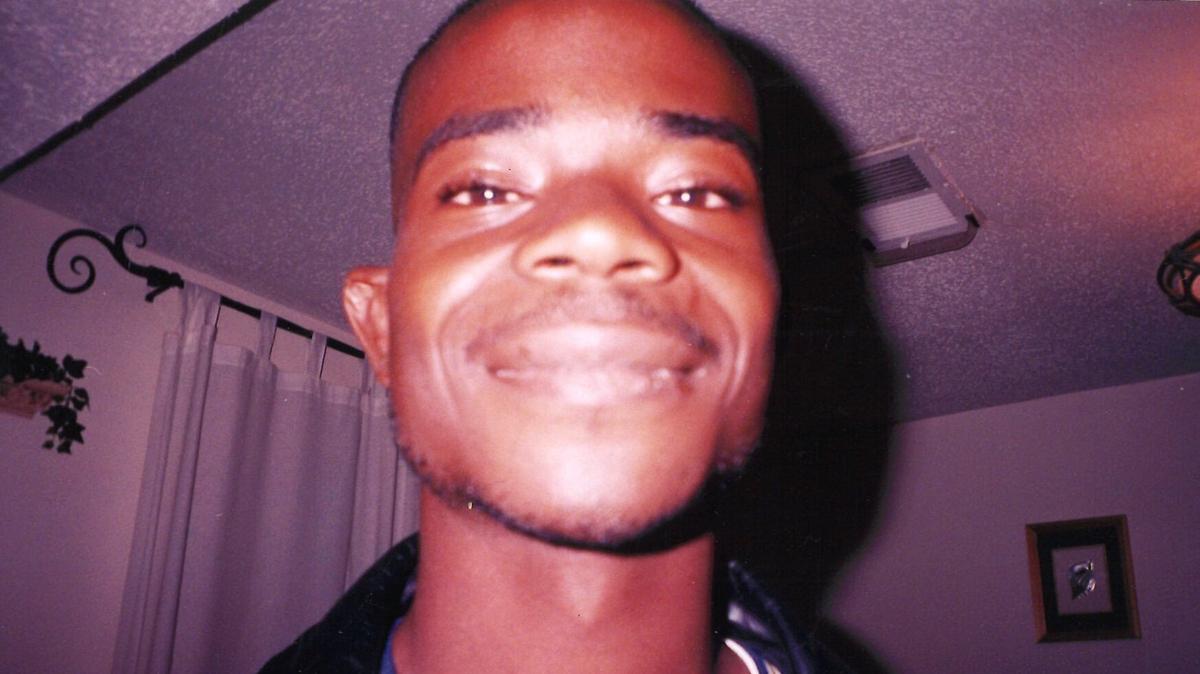

Writer and poet Clint Smith once said, "The death penalty not only takes away the life of the person strapped to the table — it takes away a little bit of the humanity in each of us." The hypocrisy of the death penalty aside, Nathaniel Woods shouldn't have been executed. A New York Times documentary, To Live and Die in Alabama, sheds light on Nathaniel's case, taking us deeper into a story that should have had a different ending. Why was Nathaniel Woods executed?

Why was Nathaniel Woods executed?

Nathaniel Woods and his friend Kerry Spencer had argued with two cops early in the day on June 17, 2004. Woods threatened one of them, Carlos Owen, who had previous run-ins with Woods as a teenager. Hours later, those same cops, along with two more, returned to the house upon discovering Woods had a misdemeanor assault warrant.

What happened next isn't entirely clear, depending on who you ask. The gist is that when the police entered the house where Woods and Spencer were, Woods immediately ran. Spencer was holding a rifle because, as he told CNN in an interview from prison, "I'm in a crack house. We sell dope. This is what we do. You always have to have your gun on you at the ready if you're inside that f--king apartment."

Spencer opened fire on the four policemen, killing three and injuring one. Eventually, Spencer made his way to a neighbor's attic where he was hiding, but in a letter Woods wrote, he said he was "found sitting on a nearby porch, apparently 'very relaxed' and carrying two .22 caliber bullets in his pocket."

Woods allegedly bragged about the shootings, despite not actually pulling the trigger. When Spencer was initially taken into custody, he didn't say anything but eventually wanted to make sure the cops understood that Woods didn't murder anyone. "I told them Nate didn't shoot nobody. Nate ran. Nate didn't even have a f--king gun," Spencer explained to CNN.

If Woods didn't shoot anyone, why did he receive the death penalty?

Woods' trial was severely mishandled and was, in a word, a farce. Despite being held in a city that is mostly Black, the prosecutors managed to secure an entirely white jury. The prosecution's argument was, while Spencer actually murdered the policeman, it was Woods who lured them to their deaths. Both Woods and Spencer were charged for the same crime, capital murder, despite the fact that Woods never even picked up a gun.

Despite Spencer admitting freely that he did it, in his own trial and again in a letter to the governor of Alabama, only Woods received the death penalty. Spencer's jury opted to sentence him to life in prison without parole. Woods received the death penalty because his jury never heard Spencer's claim that it was self-defense, and they voted 10-2 in favor of the death penalty. Alabama is one of the few states that allows a non-unanimous vote to end in an execution.

The New York Times documentary about his case explores what happened to Woods after he was arrested. They speak with family, lawyers, and family members of one of the murdered officers in an attempt to make sense of what truly makes no sense. Unfortunately, it's too late for Woods, but perhaps this documentary will chip away ever so slightly at a deeply racist justice system that failed him.

To Live and Die in Alabama is streaming on Hulu starting Dec. 3.