Andy Warhol Museum Makes the Perfect Food Bank Donation for Late Artist's Birthday

Updated Jan. 18 2019, 12:17 p.m. ET

Andy Warhol and Pablo Picasso are the two most important artists of the 20th Century.

Important’s an easy word to throw around, but Picasso and Warhol affected, influenced, and inspired so many people that they actually deserve the compliment.

Warhol, a Renaissance man who wrote a: A Novel, one of the most celebrated books of his time, directed critically-acclaimed films, gave captivating interviews, and carefully constructed a persona that fascinated everyone, was mostly recognized for his “Pop Art” paintings.

And out of all his paintings, his "Campbell’s Soup Cans" are probably his most recognized work.

We’ve seen them everywhere in all different shapes, colors, and sizes. Why a painting of a soup can would matter to anyone seems a bit crazy, but Warhol’s ability to capture and comment on the times he was living in was uncanny. It’s the reason why so much of his work defied explanation, and why it received such widespread praise.

And even though it’s been 31 years since the death of Andy Warhol, the artist is still celebrating his birthday.

Well, the museum dedicated to his legacy is anyway.

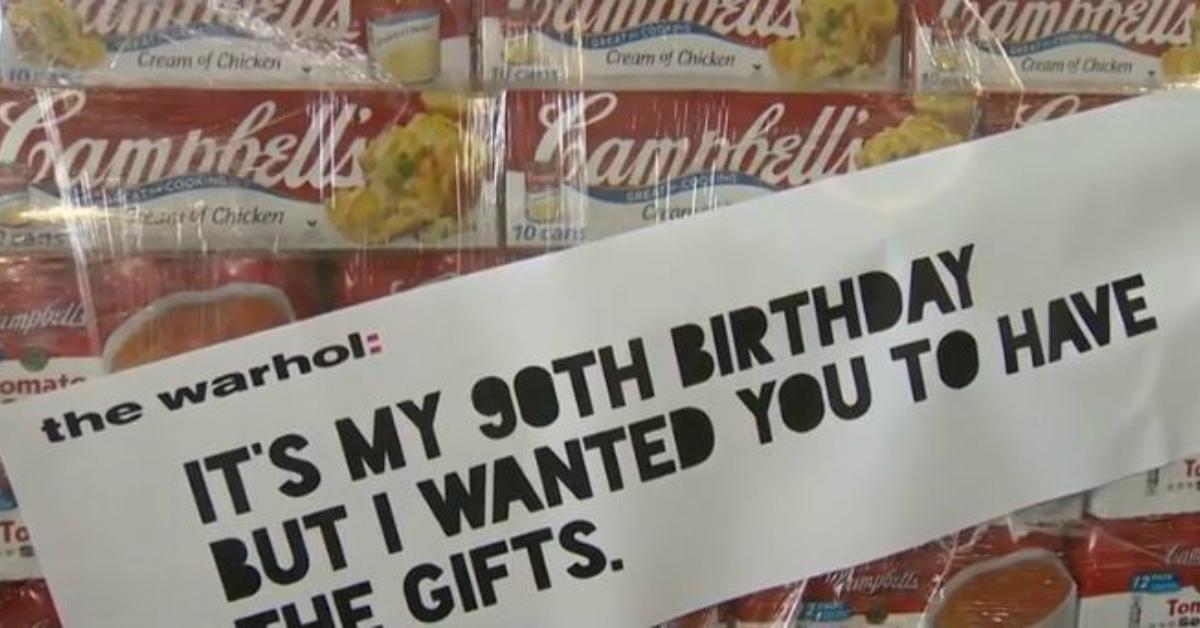

The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh celebrated what would have been the artist’s 90th birthday by donating 90 cases of Campbell’s soup to the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank.

The act was equal parts charity, art, and celebration of Andy’s life.

The food bank’s Chief Advancement Officer thought the act was classic Andy.

“He grew up in a working-class family, and he was really committed to challenging the system every day,” Traci Weatherford-Brown told WTAE.

Traci also says that although the cheeky donation is making headlines for its obvious homage to the late painter, it was a “stunt” with practical and meaningful implications.

“We know that one in seven of our neighbors — including one in five children in southwest Pennsylvania — are food-insecure, meaning that they sometimes struggle with where their next meal is going to come from. That is a stress they carry with them every day.”

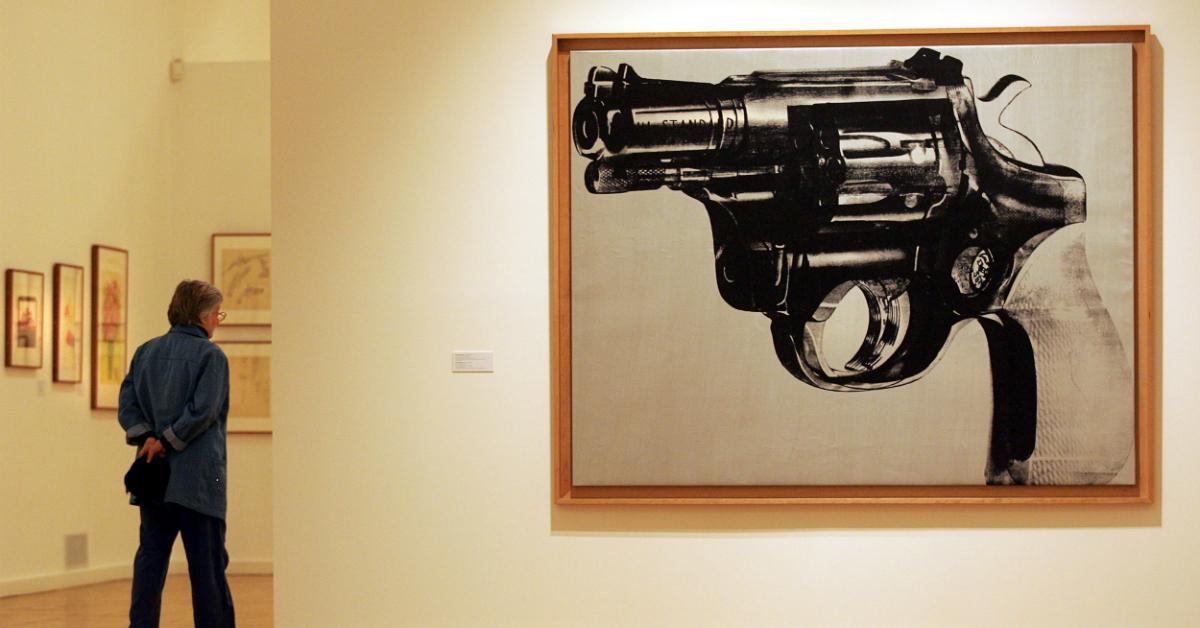

A lot has been said on the extent of Warhol’s impact on art and culture.

An Artsy article calls Warhol “arguably America’s best-known artist” and looking at his body of work, it’s difficult to argue that he isn’t.

Writer Peter Wollen summed up Warhol’s “Renaissance-man-ness,” explaining why he was so much more than just a “pop painter”:

“A filmmaker, a writer, a photographer, a band-leader (if that’s the word to characterize his involvement with the Velvet Underground), a TV soap opera producer, a window designer, a celebrity actor and model, an installation artist, a commercial illustrator, an artist’s book creator, a magazine editor and publisher, a businessman of sorts, a stand-up comedian of sorts, an exhibition curator, a collector and archivist, the creator of his own carefully honed celebrity image, and so on...Warhol, in short, was what we might loosely call a “Renaissance man,” albeit a Pop or perhaps post-modern Renaissance man.”

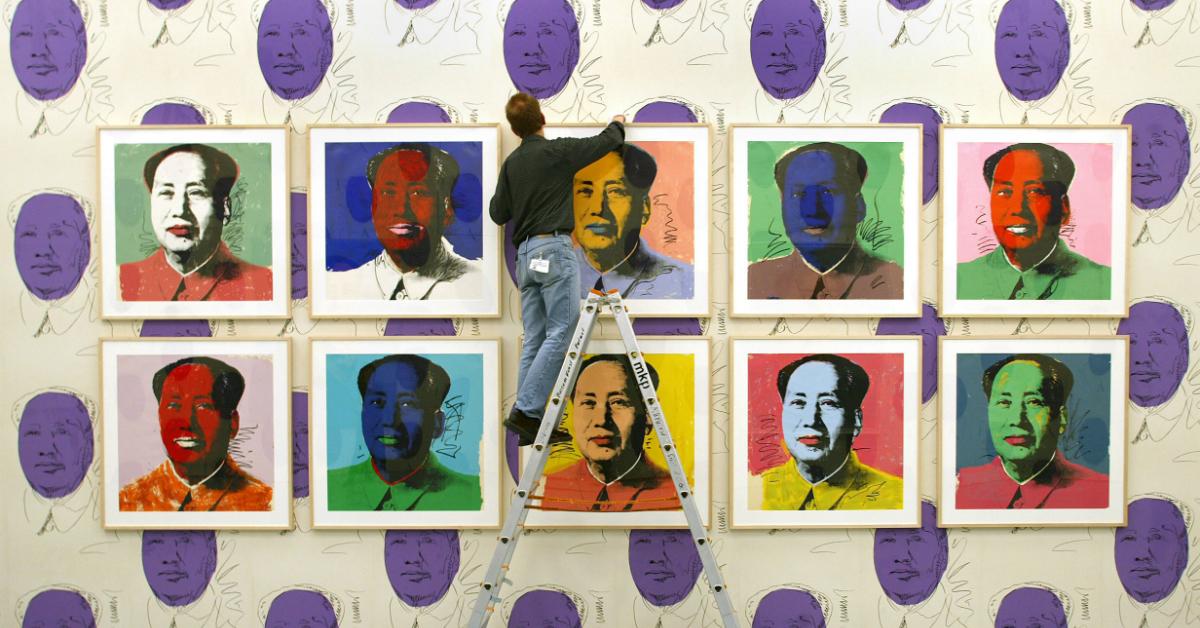

Art Historian Robert Rosenblum also argues that the work produced by Warhol between 1962 and 1987 is pretty much the best way for people to understand what was going on in that time period.

“Warhol’s art is itself like a "March of Time" newsreel, an abbreviated visual anthology of the most conspicuous headlines, personalities, mythic creatures, edibles, tragedies, artworks, even ecological problems of recent decades. If nothing were to remain of the years from 1962 to 1987 but a Warhol retrospective, future historians and archaeologists would have a fuller time capsule to work with than that offered by any other artist of the period. With infinitely more speed and wallop than a complete run of the New York Times on microfilm, or even twenty-five leather bound years of Time magazine (for which he did several covers), Warhol’s work provides an instantly intelligible chronicle of what mattered most to people, from the suicide of Marilyn Monroe to the ascendancy of Red China, as well as endless grist for the mills of cultural speculation about issues ranging from post-Hiroshima attitudes towards death and disaster to the accelerating threat of mechanized, multiple-image reproduction to our still-clinging, old-fashioned faith (both commercial and aesthetic) in handmade, unique originals.”

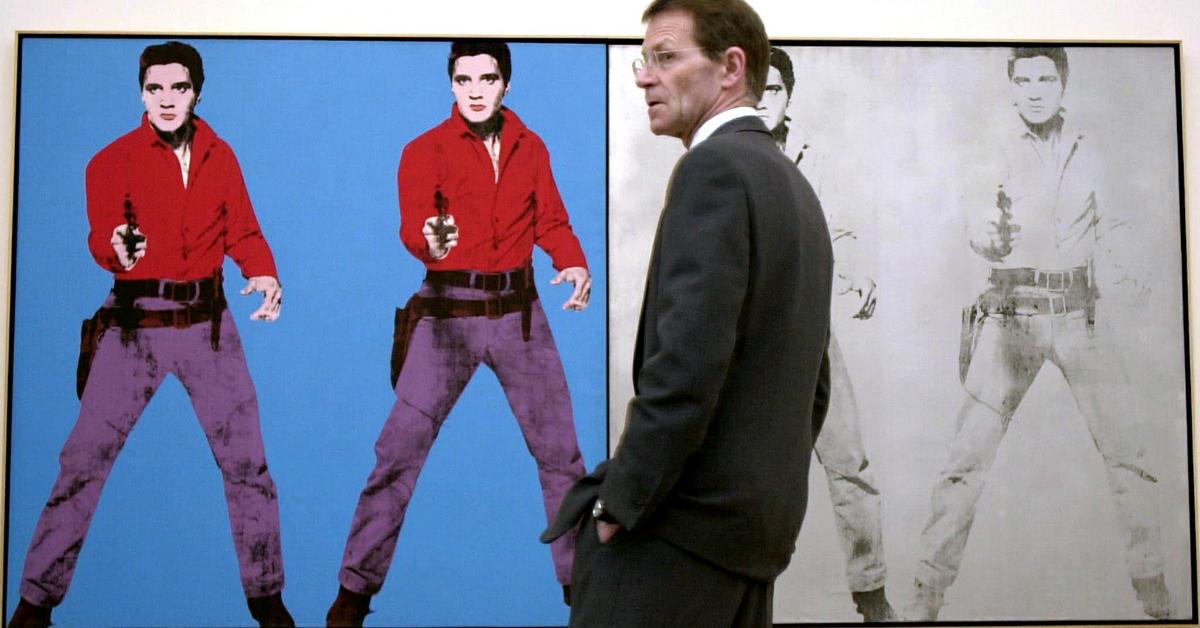

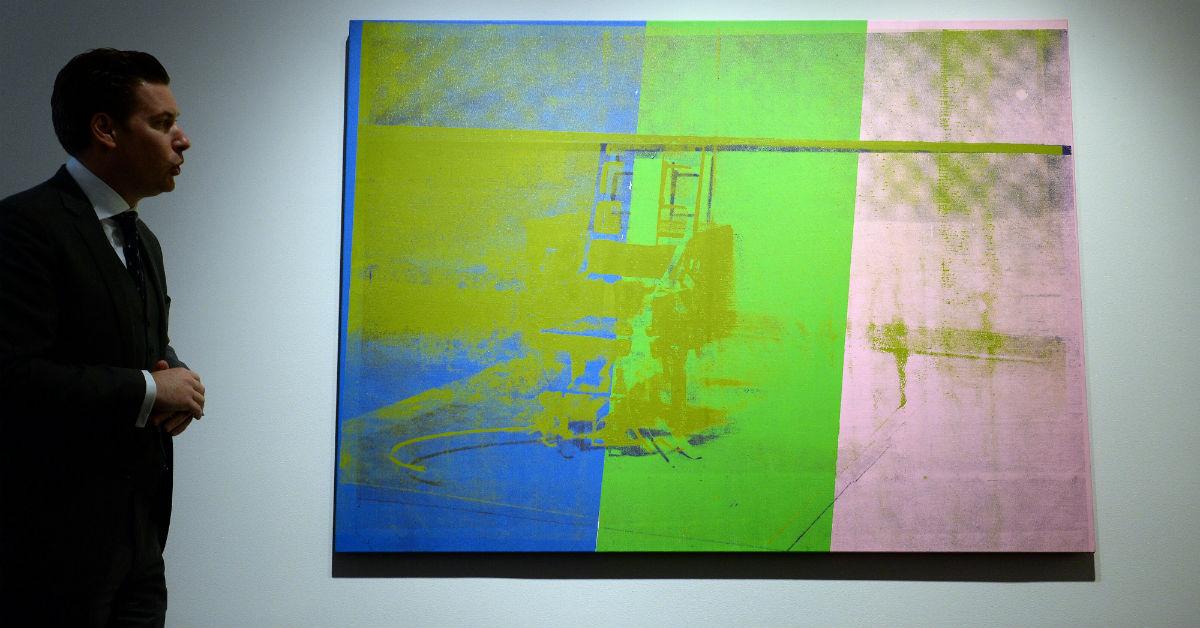

But even if you wanted to just appreciate the man’s art, then you totally could, because it’s amazing.

Damn, he's good.